Can AI Truly Replace Psychotherapists?

Empathy, Embodiment and Algorithmic Limits — A Balanced Perspective from a trained psychotherapist with a CS Background

In my time away from psychotherapeutic practice, my thoughts often turn to the rapid development of AI. I am particularly concerned with the question of its influence — both potential and already tangible — on the labor market and the future of various professions. It's already evident how AI is changing the landscape in fields related to text, visual content, and software development. This period is being compared to nothing less than an industrial revolution. The automation of certain processes raises complex questions: how far will it go? Will there still be a place for humans in these domains? And, of course, the most intriguing question — which professions will remain unaffected the longest, if any at all?

Discussions surrounding the latter question sooner or later converge on those professions where the human factor is traditionally considered an integral part.And psychotherapy is a prime example here. Increasingly, I encounter discussions and articles raising the question: can AI replace a psychotherapist?

On the one hand, acquaintances and strangers from the tech world sometimes confidently assert that replacement is already possible. On the other hand, many of my fellow psychotherapists insist on the uniqueness and irreplaceability of human contact.

I must admit, just a couple of years ago, I myself was inclined to believe that psychotherapy would be one of the last spheres to be affected by AI. However, the rapid pace of developments and critical reflection upon them have prompted me to seriously reconsider this viewpoint. A telling example: twenty years ago, people were convinced that visual art professions — design, illustration, painting — would be the last to be impacted by AI. But reality turned out to be completely different.

Today's categorical judgments about the future of psychotherapy evoke similar skepticism.

For that reason, I decided to share my reflections. Not being an expert in machine learning, I, of course, do not claim to have the ultimate truth. But as a psychotherapist with an initial degree in Computer Science, I feel a need to share my perspective, formed at the intersection of these two fields, in the hope that it will help foster more realistic expectations among both technological optimists and therapist-skeptics. The flow of news is rapid, and any predictions risk becoming outdated quickly, but I will still try to describe my vision and speculate a little on the near future of psychotherapy in the age of AI.

Recent Data

When addressing the question, "Will AI replace psychotherapists?", one cannot ignore data that attests to its capabilities in this sphere. Although the definitive answer is more complex than a simple "yes" or "no," it's important to start by examining the facts that show: people are already finding therapeutic value in interacting with AI today (the nature and depth of this value being a separate question).

Firstly, this is corroborated by a growing number of testimonials on social media, where people describe the therapeutic effect conversations with AI have on them, and how it is sometimes better than their experiences with real psychotherapists.

Of course, such social media posts can be viewed with a degree of skepticism. Often, their authors mention negative experiences with human therapists or exhibit sweeping criticism (accusing them all of indifference and self-interest), which may indicate a specific segment of the audience and their particular expectations.

However, one cannot ignore that these individuals find real value for themselves in interacting with AI, preferring it to other available options. This is supported by an article in the Harvard Business Review, where therapy and personal communication rank first among use cases for chatbots. This indicates the presence of a demand and perceived benefit, whatever the underlying reasons for this choice may be.

Secondly, new studies are continually emerging that demonstrate these claims have a fundamental basis.

For example, in one study published on January 10 in the journal Communications Psychology, scientists organized a series of four experiments. Participants were shown two messages: a written description of a difficult experience someone was going through, and a response to this message intended to support that person. The responses were written either by artificial intelligence or by professionals (crisis support specialists). Participants were asked to rate the responses based on their degree of compassion, empathy, and sensitivity.

The results of the experiments showed that responses prepared by artificial intelligence were perceived by participants as more empathetic than those from professionals. This perception held even after the author of the messages was revealed (i.e., people knew an AI wrote the message and still rated it highly).

In another very recent study from Dartmouth College (likely referring to a study involving Dartmouth researchers or the institution itself, original phrasing was "Дартмутского Института" - Dartmouth Institute), individuals with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders participated. Over 8 weeks, a group of participants interacted with a text-based AI psychotherapist, which operated according to best practices in CBT. Compared to a control group that received no support, they demonstrated significant improvements, comparable to results from conventional therapy. What's even more interesting, participants also rated the therapeutic alliance with the chatbot using the same questionnaires used to evaluate work with real therapists. And the results were comparable.

Crucial components

Undoubtedly, methodological questions can be raised about these studies as well (for example, the assessment of compassion by third parties rather than by the recipients of help). However, taken together with the prevalence of chatbot use for therapy, this data provides sufficient grounds to shake the confidence in the absolute irreplaceability of a psychotherapist. The gravity of this impact lies in the fact that the very aspects considered inherent only to human interaction, and which are deemed fundamental for successful therapy, can now potentially be replicated by AI.

We are talking specifically about empathy and the therapeutic alliance.

The fact is, numerous studies confirm that one of the main predictors of therapy effectiveness, regardless of modality, is the aforementioned therapeutic alliance. It, in turn, consists of several components, and the most important one in our context is that which is responsible for the established emotional connection. Thanks to it, the client can feel safe, seen, and accepted, and then the therapeutic process occurs.

So, the basis for building this connection is precisely empathy. Not in the everyday sense, where it implies compassion or sympathy, but in a stricter sense — as the ability to "feel into" what another person is experiencing, regardless of the nuance of that experience. So to speak, the ability to put oneself in another's shoes.

That is why the results of the aforementioned studies should be taken very seriously. If the data is confirmed, it could easily be interpreted to mean that AI can now replace psychotherapists.

Is such an interpretation correct?

Of course — in such a formulation — no. Although AI is already capable of producing a certain psychotherapeutic effect (perhaps even in a wider range than many psychotherapists imagine), this effectiveness currently has its upper limit, which:

a) is currently significantly lower than techno-optimists imagine

b) is higher than skeptics from the therapeutic community are willing to admit

c) will become increasingly fluid, and this will happen faster than most therapists realize

Below, I will try to elaborate on these thoughts.

Scale of Problem Depth

To begin with, it's worth noting that psychotherapy is not a homogeneous field. People's presenting issues are highly individual. One might loosely say that the general task of all types of psychotherapy is to help a person overcome various forms of maladaptation — an inability to interact harmoniously with the surrounding world. Simply put, some come for support in solving a specific, practical problem or to cope with troubling symptoms, while others require profound personal changes.

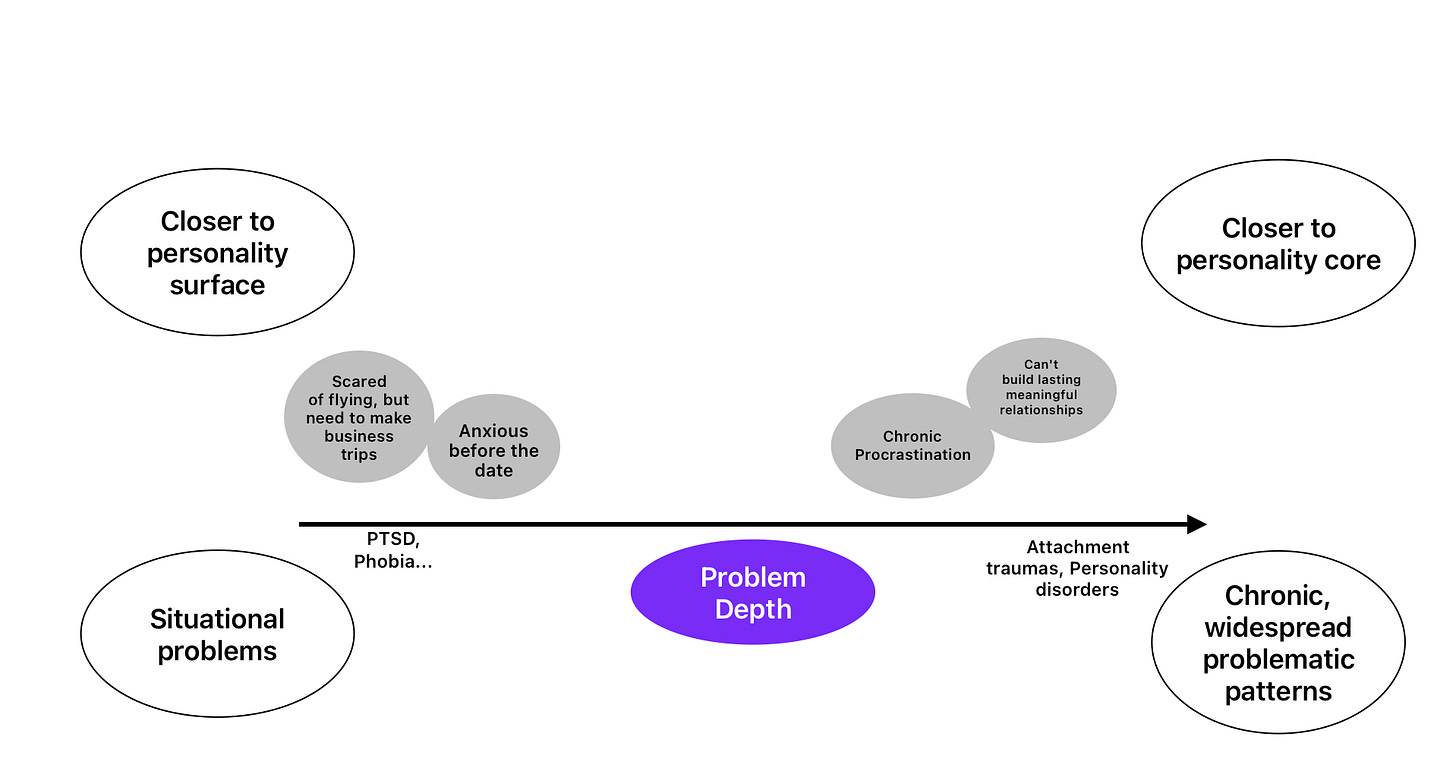

We can roughly conceptualize a scale for the depth of the presenting issue. This is not a measure of the intensity of suffering or its constancy (although some correlation with these values exists). This scale rather speaks to how deep a problem a person wants to address with their presenting issue — how long it has been familiar to them, in how many areas of life it is present, and how deeply it is woven into their character.

At one end of the spectrum are situational problems: for example, a person is afraid of flying, and now— for work, they will have to fly on business trips. Closer to the other end of the spectrum are issues like an inability to build long-term relationships, or chronic procrastination. Speaking in more clinical terms, these types include, for example, attachment trauma or personality disorders.

It is important to note that ultimately, the extent to which a problem is addressed deeply depends on the person's subjective feeling. If, when coming to a therapist, they believe that only this specific problem needs to be solved — for example, fear overwhelms them before another date — then the problem falls into the first category, regardless of whether it is actually a symptom of something deeper (e.g., attachment trauma). This may become clear during therapy, and the client may reconsider their attitude and go deeper. But they may also choose not to, and decide that resolving the symptom is sufficient for them at this stage.

Here’s an analogy: Imagine a house with cracks in the walls. Sometimes it's just surface damage from settling—easy to patch. But sometimes those cracks signal foundation problems that require much deeper work, or sometimes the whole restructuring of the building. It is up to the current occupant to decide how to deal with the issue at that exact moment.

Now, in the context of this scale, it would be good to rephrase the initial question.

Instead of "Will AI replace the psychotherapist?" — "How deep are the presenting issues that AI can help resolve?"

Empathy and Depth

To answer this, we need to return to the aforementioned correlation between the effectiveness of therapy and the strength of the established emotional connection. The same principle applies to the depth of transformation that can be achieved — profound change depends on the depth of empathy.

For clarity, consider this metaphor: the emotional connection is like a bridge stretched across an abyss, allowing the therapist and client to meet and work together. If this bridge doesn’t exist, then even in simple, surface-level issues, the interaction stalls. But if the bridge is strong and stable, it enables deeper, more effective therapeutic work..

The deeper and more subtle the problem, the more complex and sophisticated the bridge's construction must be. In a sense, in the most complex cases, where the client has never had the experience of strong and reliable relationships, the very process of building the bridge is part of the therapy, and achieving a therapeutic alliance itself signifies the completion of the work.

What is the primary tool for building this bridge?

Empathy.

The more experienced the therapist is in using this tool, the more complex bridges can be built — the stronger and lighter ropes can be thrown across greater chasms.

And one can assume that it is precisely the degree of mastery of the skill of empathy that is the narrowest bottleneck on AI's path to replacing the psychotherapist.

How Well Does AI Master Empathy?

(Before continuing, an important note: of course, AI as such does not possess empathy. Or rather, we cannot know this for sure. We can only say that it is very good at imitating it)

Understanding this, we can rephrase the question again, breaking it into two:

How developed are the empathy skills demonstrated by AI?

How deep are the problems that can be solved with such a level?

My opinion on the first question is as follows:

Today, state-of-the-art (SOTA) LLM models demonstrate empathy skills at least comparable to those of helping professionals, but with one critically important caveat: this pertains to interaction via text! That is, in textual communication, models are capable of reading and expressing emotions as well as humans can do it through text.

In this sense, I believe the results of the aforementioned studies. I base this on my own experiments and observations of others' interactions in this vein with ChatGPT 4.5 or Sonnet 4, and studying the results of the EQ3-Bench benchmark, which measures "emotional intelligence”.

Let me reiterate: the key point is that we are talking specifically about textual, or perhaps better said, verbal communication. And this leads to the answer to the second question: in such a form, even when interacting with the very best psychotherapist, it is impossible to resolve issues related to changes at deep levels.

The Nonverbal Component

The fact is, empathy originates in nonverbal, bodily processes that reflect human experience, and language is already a symbolic representation of this experience. When we say words like "sad," or "safe," we are referring to a known experience that should be familiar to the other person. When transmitted through words, of course, some information is distorted, but for everyday communication, this is sufficient. However, for building a closer emotional connection, greater precision is needed.

To understand this better, one can turn to that stage of our lives when we do not yet sufficiently command the linguistic apparatus. Research (notably by Allan Schore and Daniel Stern) shows that at this age — approximately up to two years — a critically important process of affective co-regulation occurs. The mother (or other primary caregiver) helps the child regulate their affects, using nonverbal aspects for this: voice intonations, prosody, facial expressions, bodily gestures, the nature of touch, pauses, etc. This happens in both directions — the mother not only generates these reactions but also skillfully reads them in the child's manifestations. The criticality of this interaction lies in the fact that it is precisely during this process that a bond is formed between the child and the mother, and attachment is developed. A person's future ability to regulate their affects and build emotional connections with other people in adulthood depends on this (Attachment and personality disorders — some of the deepest issues, closest to the personality core and most difficult for therapeutic work — originate precisely in disruptions of interaction at this stage)

One could say that in this interaction, the mother's nervous system, in a sense, becomes an extension of the child's nervous system — its computational power is "loaned out" to help the infant process and assimilate new experiences.

Therapeutic work with deeper personality structures is conducted in a similar vein — with greater reliance on nonverbal interaction. And the therapist, in much the same way, provides the client with the computational power of their own nervous system.

So, returning to our silicon computers, we can certainly say that a representation of the client’s situation can be loaded into them—using the client's language and words. This representation will, if lucky, be unpacked based on some previous training experience and, in response, AI therapist will offer its reasoning on the matter. In non-deep issues, this works. But the less a client recognizes their own experiences, the less accurately they can convey them verbally. What’s more—sometimes they are not even aware of their existence. So at deeper levels, this is like trying to rebuild a building merely by redrawing its blueprints. Moreover, the blueprints are based on the client's words.

Therapeutic changes are possible precisely because the therapist receives for processing not only the representation of the situation from the client's words but also a rawer data stream, including all those same nonverbal manifestations — posture, intonation, prosody, and other nuances.

Based on the above, it should be clear that AI will not be able to replace a therapist until it can operate with nonverbal signals in real-time.

So, in this sense, techno-optimists who claim that psychotherapists are about to be replaced are mistaken.

Nevertheless, psychotherapists also rely too heavily on this limitation and believe that it will be present for an indefinitely long time.

Zone of Proximal Development

Thus, many psychotherapists believe that AI is fundamentally incapable of capturing hidden nuances in nonverbal interaction. For example, a long pause from the therapist, which in some cases can be the only correct intervention. Or intonational subtleties from the client (words express agreement, while the intonation shows slight hints of irritation).

Ultimately, all this leads to the question of whether AI can approach received signals creatively and go beyond something already familiar (insights).

I understand these assumptions, but I believe this is a misconception that has been present in other areas as well. It was thought that models would not be able to operate with complex concepts about the surrounding world that they were not taught. Nevertheless, time and again, they refute this belief. During training, with an increase in computational power and the volume of data on which they are trained, new (emergent) abilities arise.

Therefore, there is reason to believe that if a sufficient amount of training data is collected, models will be able to reproduce all those implicit processes that occur between client and therapist on a nonverbal level.

What kind of data should this be?

I think it will be enough to collect a sample with visual and auditory components. These are sufficient for working via video call, and therefore, for working with deep-seated issues. That is, if a model is capable of expressing and reading visual and auditory aspects fully, then it will be able to work with nonverbal processes.

Already now, in the field of visual communication, models are quite good at recognizing emotions expressed on the face or in posture, and also quite good at generating them, but they still struggle with subtler nuances. Moreover, current technologies do not yet allow for operating with this in real-time.

With auditory signals, there are also very good results — OpenAI's advanced voice mode, Sezamme, Gemini Native Dialogue. They operate not just with linguistic constructions, but with shades of voice, prosody, tonality, etc. Furthermore, these models are already much closer to working in real-time. You can interact with Sezamme, for example, and see that in some cases, it can be very difficult to distinguish its intonations from a live person. They were most likely trained on millions of hours of podcasts.

It remains to integrate this data by training models on something like video recordings of therapy sessions. There is a difficulty with this process — there is no well-labeled data showing which intervention works and which does not. This is partly because therapists themselves have difficulty agreeing on what works and what doesn't, and it's unclear over what horizon to measure this (did it work in the moment, but strategically?). On the other hand, a notable feature of the therapy process is that a dialogue occurs, meaning we can observe the dynamics of interaction at any interval (even if it leads nowhere). This means that every intervention has a response.

Is there such an amount of data at the moment? I don't think so, but I suspect that this issue may soon be resolved, especially considering services like BetterHelp, etc. One of the crucial questions, of course, is confidentiality.

How far can delving into this technology take us? I don't know. But my prognosis is that it can go far enough to help solve a very large layer of presenting issues quite deeply. If, at some point, architectures appear that literally use embodiment (reliance on bodily sensations) and do so in real-time, then the question of replacing the therapist will already pale in comparison to the question of what distinguishes AI from humans.

Conclusion

In summary, it is important to emphasize: Even the current capabilities of AI already allow for covering a very large percentage of initial presenting issues to a psychotherapist. The fact that the depth of their resolution will not be as great does not in any way diminish how much the technology can help to significantly clear out the Augean stables that represent the state of mental health in modern society, and this can only be welcomed. Not forgetting, of course, that this requires oversight, "supervision," and further guidance from the professional community.

I would also stress that above I focused my attention on the element of empathy and somatic resonance; however, there are other important points, for example, the briefly mentioned inability of AI to ask new questions, or a phenomenon such as Sycophancy — when the model tries to please the user (one might call this confluent behavior) — which obviously severely limits serious work where confrontation is inevitable. Nevertheless, I believe that the issue of somatic resonance is the narrowest bottleneck in this whole story, and, perhaps, partly resolves the other issues as well.