Insoluble Situations

In my previous post about the paradoxical theory of change, I addressed a common assertion echoed in many spiritual and philosophical traditions and psychotherapy schools: acceptance is the key to healing from suffering.

At the end, a reasonable question was raised:

what can be done to help someone reach a place of acceptance?

This is a challenging question to answer, but to begin, I would suggest first examining its premise.

The question implies that the person is in a situation that causes them suffering, yet they continue to cling to it. It’s reasonable to assume that this type of situation is what always drives people to seek psychotherapy.

And I would argue that such situations are always chronically insoluble.

This means that the person sees no way of resolving it, despite trying for a long time (even a lifetime). Sometimes the person may not even be aware that he or she is making these attempts. This is made worse by the fact that a person is often not fully aware of what the situation is all about. There is simply a vague feeling that some part of their life has become a stagnant pond in which suffering is gradually beginning to blossom. And it is one of the tasks of the therapeutic process to help clarify what this part is (contrary to a common misconception, it is not necessary to come to psychotherapy with a clearly formulated problem—it is enough to have the feeling that there is something unsatisfactory in one's life).

But overall, no matter whether one is aware or not, these are the same insoluble situation.

And I would suggest, that to partially answer the above question, we need to better understand how these insoluble situations are structured.

Exploring the Structure of Insolubility

For this purpose let’s take some particular example — experience of abandonment. I think it is no exaggeration to say that this is one of the fundamental issues that arises quite often in the therapeutic process.

The essence of this situation can be conveyed through a rather vivid image that is often found in art, dreams and client descriptions. Below I will describe a kind of collective essence of this image.

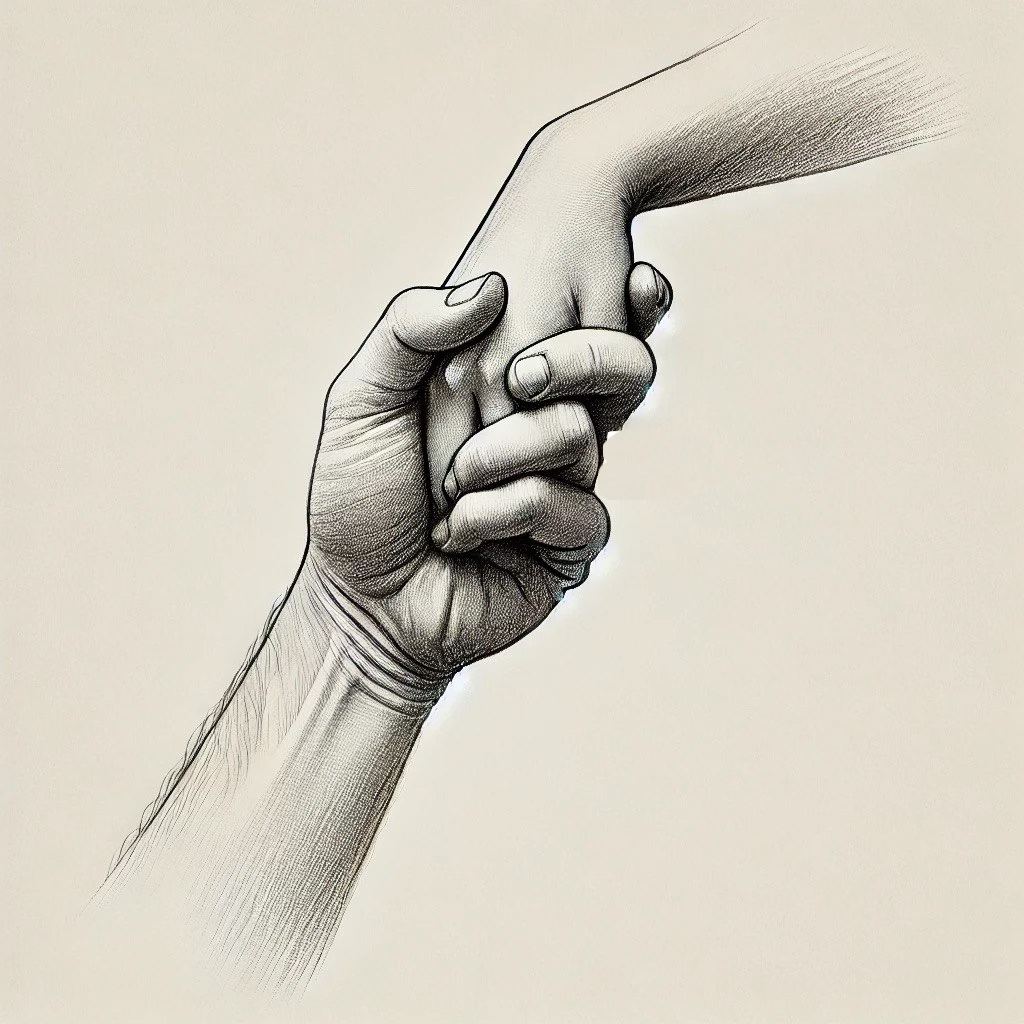

Imagine two people: to avoid confusion in the description that follows, we will say he (the client) and she, although gender is completely irrelevant here. She decides to leave him and he desperately holds her, trying to stop her from leaving. But she is gradually freeing herself. With each passing second, her departure becomes more irreversible, making him squeeze his hand tighter and tighter. But no matter how hard he tries, it's never enough to hold her. So she continues to slip away, inexorably approaching the moment of separation. And this process goes on forever, reminiscent of Achilles' endless attempt to catch up with the tortoise, or the agony of Tantalus and Sisyphus. There is a lot of anxiety, despair and tension in this image, trying to get to some kind of resolution, but it never comes.

Uncovering the Layers

It is important to remember that this is just an image. Not the situation of abandonment itself, but its model, its representation, the way one sees it (even if one is not aware of it).

Nevertheless, this mental image influences a person's real life by structuring similar situations in this way. In the most severe cases, a person can superimpose this image on even the most innocuous situations and feel abandoned in them. For example, a colleague at work said the word 'hello' a little more dryly than usual. Not to mention more complex relationships where one might actually leave.

It is also important that this image contains a lot of physicality, because it is at the physical level that all our unassimilated, emotionally charged experiences are stored and then reproduced. So the tension implied in this is constantly present in a person's background. If he is aware enough, he may even find that he is experiencing this tension on a physical level. For example, as if his hand were really frozen in this endless process of compression, afraid to let go. And it would be all right if it was his real hand. Then he or the therapist could just release it physically. But the clenched hand is of a different nature. It is in a separate reality, something like the phantom limb from Ramachandran's experiments. A person would like to unclench it, but has no control over it.

This brings us to the first layer of insolubility: the gap between reality and the mental image trapped in the person’s mind. The inability to align perception and behavior with the actual situation creates a tension that resists resolution. This misalignment forces the person to interact not with reality, but with a model that perpetuates their suffering.

But the question naturally arises. Our minds are designed to reject models of the world that do a poor job of predicting reality. So how is it that a person chooses to stay with this particular view of the situation, despite the endless suffering that is inherent in it?

What is it about this image that makes it a trap that is so difficult to escape?

To answer this, let us look again at the situation described. We can see that the one who is being abandoned is focusing on a rather obvious idea: if one squeezes his hand hard enough, the other will not be able to get away. A perfectly reasonable idea, based on our experience of the material world. On this basis, you are essentially trying to answer a question: 'Do I have enough strength to hold the other?

And there is a problem with that question.

It lies in the fact that there is no definitive answer. After all, if strength is not enough now, will it be possible to become stronger and still hold on later? And vice versa, if strength is enough now, will it be enough in the future? The hope and fear that accompany each of these states make one swing like an endless pendulum.

This can be highlighted as a deeper layer of insolubility: the presence of two polarities (in this case: weak-strong) that create an endless cycle. Once at one pole, one immediately begins to feel the pull to the opposite pole and the situation cannot be resolved.

This description gives a clearer understanding of the structure of insolubility. But to stop at this level would be to miss the deepest part of the trap.

Hidden Layer

Apart from the fact that the question described above - "Will I have enough strength to hold the other?" - cannot be answered definitively, it contains an even more insidious trap.

Every question we try to answer must have a true premise at its core. This can be seen in the famous loaded question '"Have you stopped beating your wife? Trying to answer that question directly would mean accepting the premise - as if it has always happened.

The same thing happens in our case. The question - will there be enough strength to hold on? - implies a priori that the one who is left holds the other in the first place. And when this assumption is suddenly questioned, there is strong resistance. Because this very premise is very comforting. It creates the illusion of control and makes the person believe that he or she just lacks the strength to hold on.

Such a vision protects him from facing the real tragedy of the situation: he's got it all wrong. If anyone in this situation is free to choose the strength of their grip, it is the one who has chosen to let go. She was holding on, and now she's letting go because she can't or doesn't want to hold on any longer. And it's obvious that the one who stays has no control over this. His fantasies about how tightly he needs to hold the other are in fact—as in a distorted dream—a reflection of his own desire to be held tightly. The phantom hand that he could not control was not really his, but that of the one who was leaving. The person was confused as to which side of the interaction he was on. (which side of contact boundary, using Gestalt Therapy terminology)

I think this is the most important layer of the intractable situation. Confusion about which roles and possibilities I identify with and which I alienate myself from. Who I am in this situation and what I can and can't control.

Once this perceptual confusion is resolved and everything falls back into place, we get a completely different situation. It ceases to be unsolvable. Not because a solution is found, but because the structure of the problem itself changes. The realisation that another person's hand can and, more importantly, wants to unclench freely dissolves the agonising spasm in which the phantom hand is frozen. The energy that has been spent essentially in disembodied attempts to grasp the void more tightly is transformed and redirected to an area that has a real chance of growth and change.